Pythagoras, Pattern & Islamic Art: Uncovering the mystery & history of the world we live in through Sacred Geometry.

Islamic art is steeped in history, tradition, and religious symbolism, with every design element carefully chosen to convey a particular message or idea. It is renowned for its intricate designs, and beyond the aesthetic beauty lies a deeper layer of meaning and symbolism.

Read on as we explore the use of patterns, focusing on the intricate world of geometry, Pythagoras' influence on Islamic art, and the golden ratio. Additionally, we will examine Uzbekistan's famous Islamic architecture and the history of astronomy to gain a better understanding of how symbolism and mathematics are used in Islamic art.

Tilli-Kara Mosque interior dome in Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

Wandering through the ancient cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, viewing intricately decorated structures, it’s hard not to become intrigued by the patterns adorning entranceways and interiors.

The intricate mosaics and elaborate hand-painted designs adorning the walls of the mosques, mausoleums, and madrasas transport visitors to a bygone era of opulence and grandeur. These decorations contain many symbols, some hidden and others more obvious, including the recurring eight-pointed star often in adjunction with the six-pointed and five-pointed stars.

The entranceway to Abdulaziz Khan Madrasah in Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

One can only wonder if there was more meaning to these stars and symbols rather than them merely serving as decorations and if it isn't a coincidence that they fit perfectly together.

In Islamic art and architecture, the depiction of living beings is looked down upon. For example, it is believed that if an artist were to paint the image of a man on the wall of a madrasah (religious school), this would distract the viewer from the true meaning of the place of worship, leading to worship of that figure rather than God.

Due to this belief, figures are instead replaced by geometric patterns.

Although there is an absence of figures in Islamic art, there are two 17th Century madrasahs standing still within Uzbekistan, that depict living creatures.

The Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah in Bukhara features the Simurgh, a mystic phoenix, and the Sher-Dor Madrasah in Samarkand features a pair of tigers with a sun rising above their backs. It is not clear still why these images were shown on these structures, though there is some speculation the animal-sun of Sher-Dor reflects the tenacity of pre-Islamic Zoroastrian solar symbolism.

The Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah in Bukhara.

Sher-do Madrasah, Samarkand.

In Islamic culture, life begins with and centres on Allah. So then, the use of geometrical patterns in Islamic art is believed to lead the viewer to an understanding of the underlying reality or truth of life and to bring them closer to God.

The eight-pointed star (Rub el Hizb) is featured in most patterns adorning Islamic structures. This is a symbol of the eight gates of heaven. Universally the eight-pointed star symbolises balance, harmony, and cosmic order. When the star also includes a circle and/or a flower inside it, this symbolises duality and the masculine and feminine.

Examples of eight-pointed star Rub el Hizb.

There is no doubt that as Uzbekistan was at the centre of the Silk Road, it was shaped by the many different cultures passing through. Countries traversed by the Silk Road became melting pots in which many cultures could share their ideas and beliefs.

Symbols such as the eight-pointed star appear everywhere from Buddhism to Christianity. Worldwide one will find that Geometry is the language of the universe as it can be seen everywhere in nature, in the stars and in the movement of the planets.

Mary with eight-pointed star from Jacob de Backer’s 16th Century painting - The Nativity and a Buddhist mandala also 16th century.

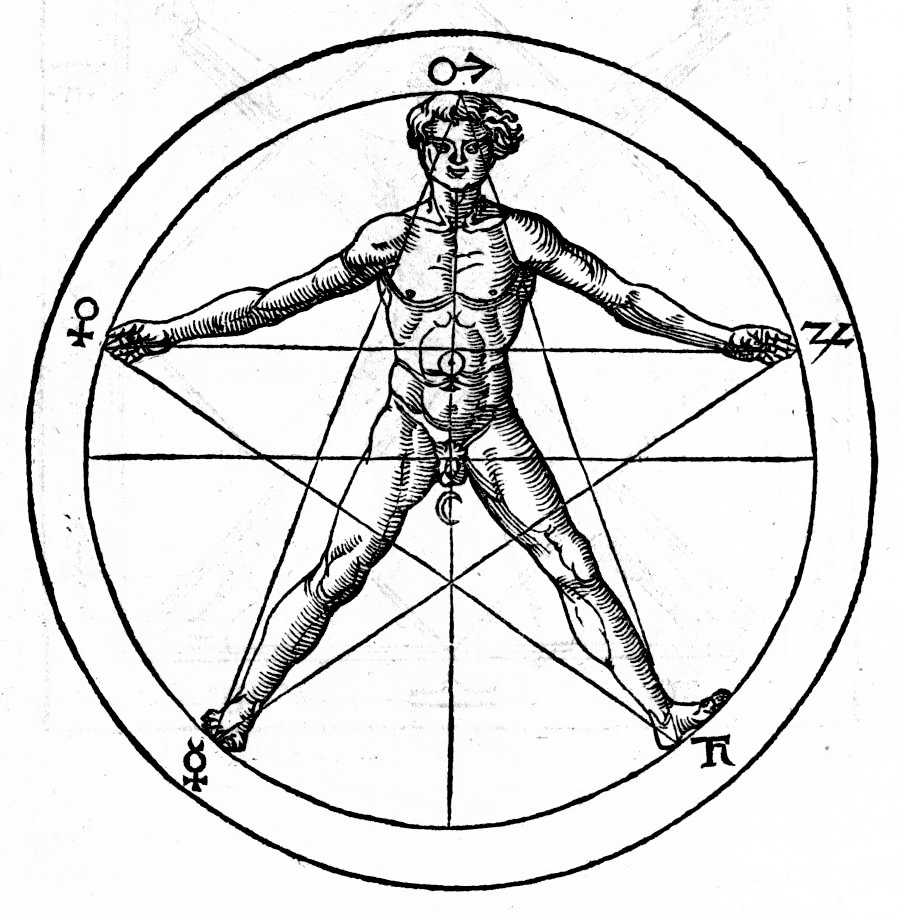

It is worth noting then, the connection between the numbers eight and five when on the subject of symbolism. These numbers each correspond to the planets Mars (eight) and Venus (five), both of which are universal symbols of masculine and feminine.

As Venus conjuncts with the sun over a period of eight years, it traces out a star, or pentagram as it is commonly known, along the zodiac belt. This symbol was discovered around 6000 B.C.E. in the Tigris-Euphrates region of the Middle East through astronomical research.

This is also known as the Heliacal rising pentagram for Venus.

Detail from James Ferguson’s, Astronomy Explained Upon Sir Isaac Newton’s Principles, 1799 ed., plate III, opp. p. 67.

Ulugh Beg (1394-1449 A.D.), the last remaining grandson of ruler Amir Temur and heir of the Tamerlane empire. He was a keen astronomer, mathematician and scientist. His observatory was the largest and greatest ever built at the time and featured an instrument that could measure the length of the year within 25 seconds of the actual value.

This great meridian arc was able to determine the axial tilt of the Earth accurately enough that the numbers recorded would be accepted for today's modern range of values.

Ulugh Beg's scientific discoveries and achievements included recording 1,018 stars and their locations in the night sky. This was before the invention of telescopes.

Frontispiece of the star catalogue (1690) of the Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius honouring the great astronomers of the past. Ulugh Beg is seen seated to the left of Urania.

The constellation of Virgo from Ulugh-Beg's manuscript 15th Century.

Just like those before him, he was intrigued by the mysteries of the universe and how the placements of the stars correlate to our life on Earth.

So what is the connection between Islamic art and Pythagoras?

Islamic artists developed their style through an interest in the golden ratio, popularised by Greek Mathematician, Pythagoras. The golden ratio is found everywhere in nature and symbolises harmony and balance - without these qualities one would not attain enlightenment.

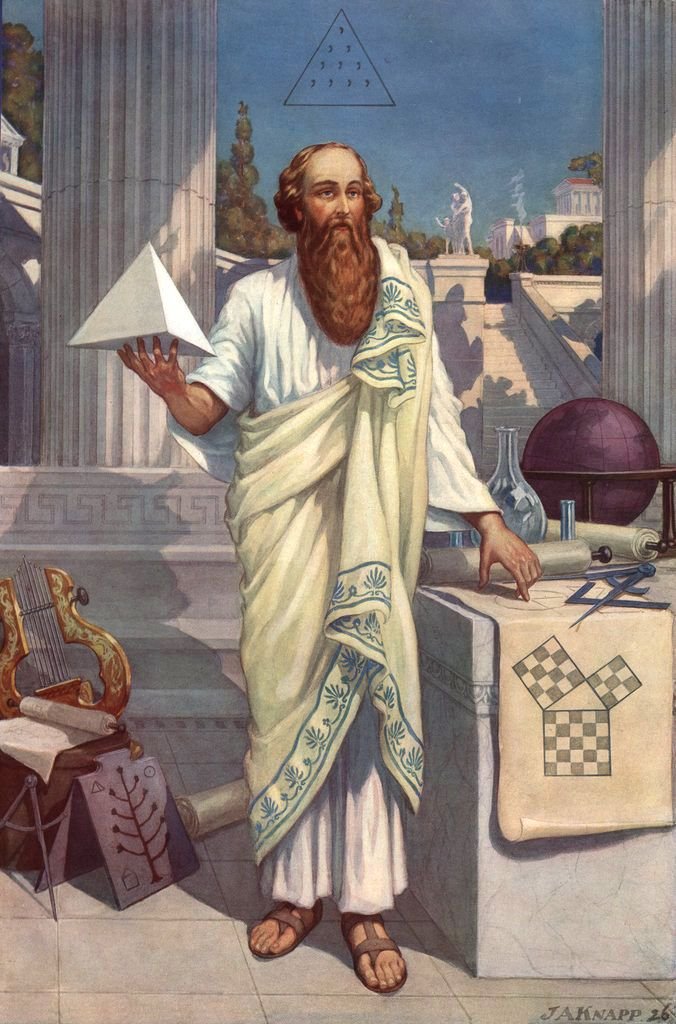

Pythagoras by J. Augustus Knapp, circa 1926

Pentagram and the human form.

Pythagoras (c. 570 B.C.E. – 496 B.C.E.), the Greek mathematician and mystic saw the pentagram as mathematical perfection. This later became known as the Golden Ratio. Pythagoras’ followers were seekers of knowledge and truth. Initiation into the Pythagorean brotherhood was incredibly strict, including a five-year vow of silence, absenting from eating meat and giving up their worldly possessions. Once initiated into the secret society, Pythagoreans would identify themselves by using the symbol of the pentagram.

The Golden Ratio can be found in the structures of all living things on earth - plants, flowers, and the human form. During Pythagoras' time, the pentagram represented the five points of a human being: two feet, two hands, and one head. It was the Golden Ratio that was used to build many of the mightiest structures on earth including the Great Pyramids, Taj Mahal, Notre Dame and the Parthenon.

Pythagoras was interested in what gave order and harmony to the elements of the world and influenced a lot of what we see in the world today. He believed that number rules the universe and it is not what is to be determined but what determines.

Detail from Shah-I-Zinda mausoleum, Samarkand.

Shah-i-Zinda mausoleum, Samarkand.

Islamic art isn't interested in realistically replicating nature but rather hints at the greater purpose of life. Through its geometrical patterns, Islamic art invites the viewer to understand the universe and to become closer to God. In other words, Islamic art reflects the Golden Ratio, of cosmic order and harmony.

Both Pythagoras and Ulugh Beg's discoveries gave a scientific explanation to what might have been seen, back in ancient times, as a mystery. They brought us closer to an understanding of why things work the way they do.

In conclusion, the use of symbolism in Islamic art is a reflection of the deep spiritual and cultural values that have shaped the Islamic world throughout history. The incorporation of mathematical principles such as the golden ratio, also studied by Pythagoras and his followers, speaks to the Islamic tradition's deep appreciation for the harmony and balance found in the natural world.

Uzbekistan’s preservation of Islamic art and iconic buildings offer a glimpse of this intricate geometric pattern, calligraphy, and symbolism. This preservation of history the country offers has been influenced by various cultures and dynasties, which have contributed to its unique character.

Still to this day, the beauty of pattern, Pythagoras and the Silk Road continues to inspire and captivate people from all over the world and draws us closer to the answers we may seek.